Liar's Dice

A Quick Demo for Analyzing Liar's Game

This is a brief analysis of the popular drinking game Liar’s Dice. Whenever I attend karaoke events and I am invited to play this drinking game, people often say “Charles, stop calculating”, just because I study mathematics. The truth is I never thought about performing any calculations; I just want to have a good time. However, typical stereotype has encouraged me to start exploring and analyzing this game.

Game Introduction

For those who are experts in this game, feel free to skip this section.

I will first explain some game rules and assumptions for this analysis. The game consists of \(n > 1\) players and each player has a cup with 5 dice in their cup. Initially, each player will shake their dice in their nontransparent cups, hiding the results from other players. Subsequently, a player starts guessing the number of dice that is present at an aggregate level. For example, a player can say “3 three’s” to indicate that he/she believes there is at least a total of three 3’s amongst the n players, including oneself. The next player can choose to believe that it is the truth or they can doubt it. In the case the next player believes there are three 3’s, then the player must continue guessing the number of dice present on aggregate, with the rule that either the number of dice or the face value (or both) must be bigger than the previous claim. For example, if player 1 says \(n_1\) \(m_1\)’s, if player 2 believes, then player 2 must say \(n_2\) \(m_2\)’s where \(n_2>n_1\) or \(m_2>m_1\). For example, if player 1 calls 2 3’s, then player 2 calls a raise on the quantity of 3’s (3 3’s or more) or call a raise on the face value of the dice (2 4’s or 2 5’s or 2 6’s).

The game continues in this fashion until a player refuses to believe the previous claim, at which everyone reveals their dice count for the truth. If the claim is correct, the last person has to drink, otherwise the previous player drinks.

In this gameplay, there are several special rules:

- 1 is a wild card that can be counted as any value. For example, if someone says three 3’s, we also count the 1 as a 3.

- No one will have 5 distinct dice. If one rolls 5 distinct dice, they must reroll. They have 2 chances to reroll before it is considered as a lost and they have to drink.

- If one has 5 of the same dice (it can include 1’s, say someone has the outcome 5,5,5,1,1), it is counted as an outcome of 6. (For the example, it would mean they have five 5’s)

There are additional game rules that will affect the operations of this game, but to analyze the probabilities, this basic set would suffice. For a more comprehensive set, please check out Liar’s Dice

Approach

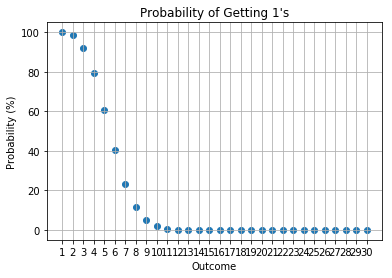

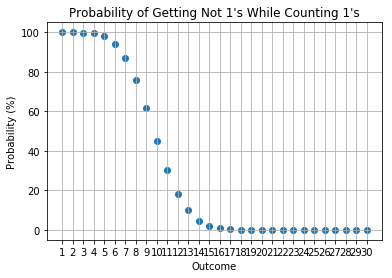

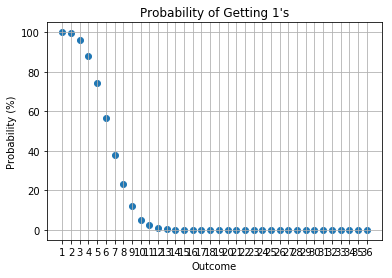

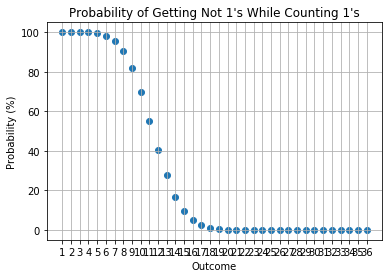

In a \(n\) player game, you can see your dice rolls, so you would be interested in the probability of the counts of other \(n-1\) players’ rolls. In particular, we have created a demo notebook to calculate the probabilities. The approach uses Monte Carlo simulations to estimate the probabilities of interest. The reasons why binomial (or multinomial) distribution is not used for calculations is that the number of outcomes is not a binomial (or multinomial) problem; rules number 2 and 3 above make the probability non-binomial (or non-multinomial).

Results

We present the results for when there are n opponents, \(1<= n<= 6\).

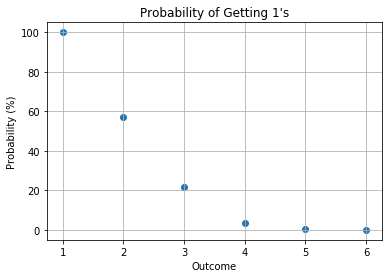

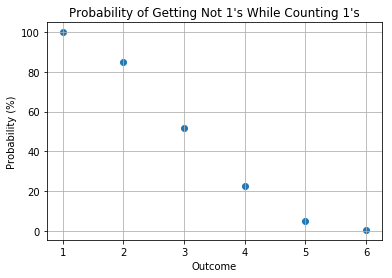

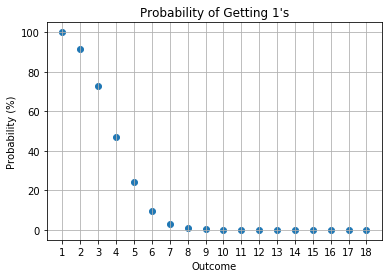

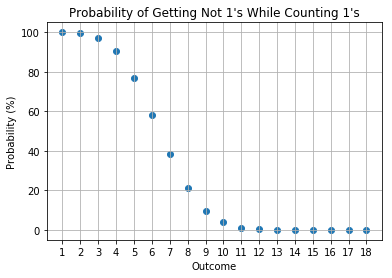

1 Opponent

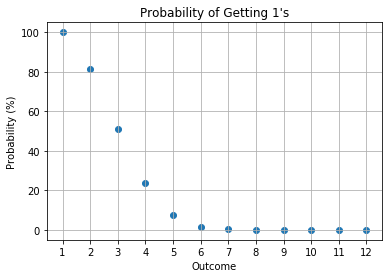

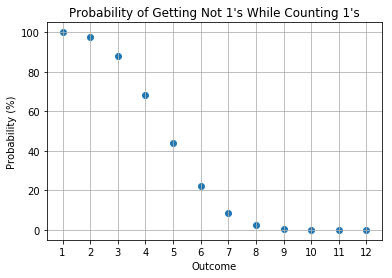

2 Opponents

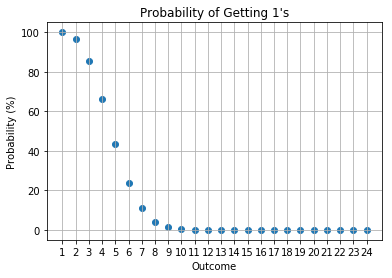

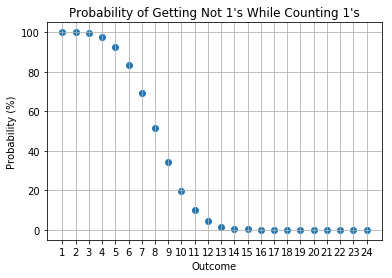

3 Opponents

4 Opponents

5 Opponents

6 Opponents

Potential Future work

Issues for the current approach is that I am using a Monte Carlo simulation and I did not set a convergence threshold to wait for convergence. I have naively set the number of simulations to be 10,000. This causes some instability to the probabilities as can be seen within the notebook. The proper way to perform a Monte Carlo simulation is to set a convergence tolerance. I did not do this due to the nature of the quick demo. Nonetheless, the results present a good proxy of the actual probabilities.